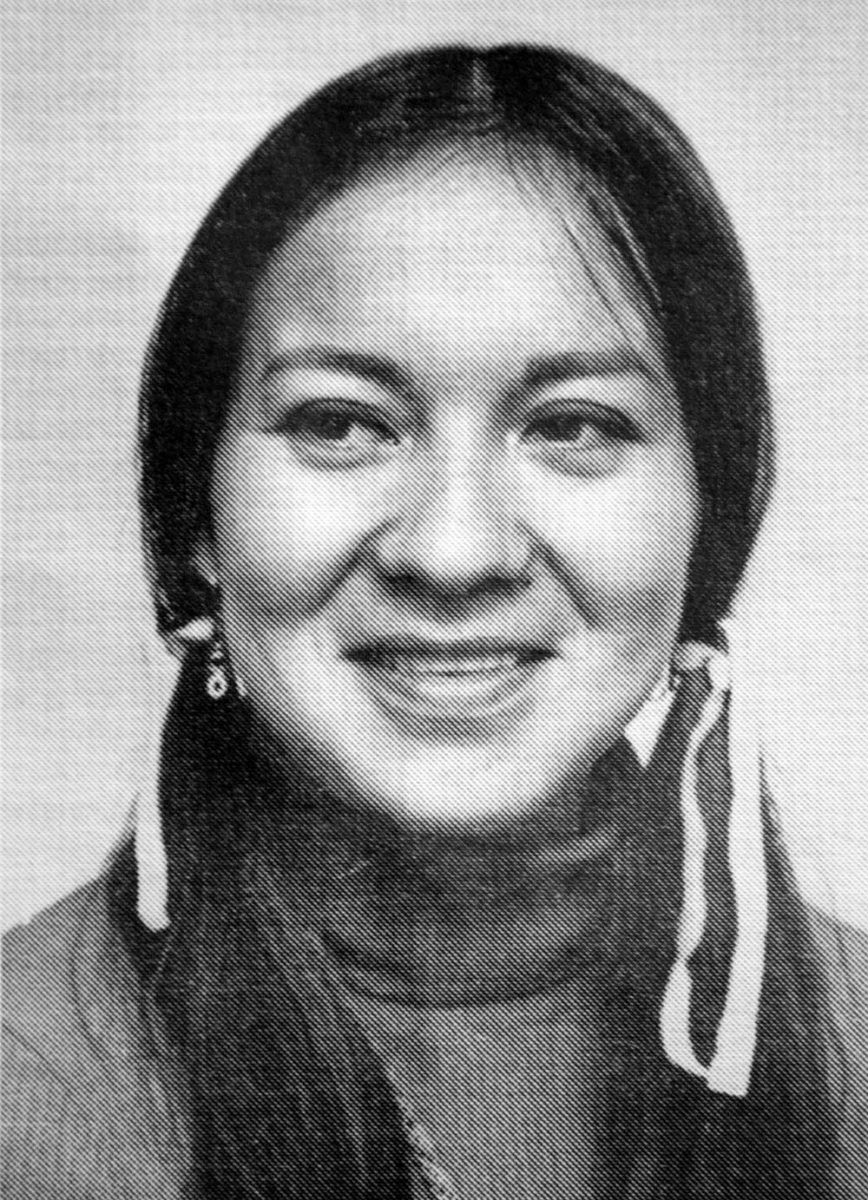

Dr. Jeannette Corbiere Lavell, C.M. (Member of the Order of Canada)

Adversity compelled this brave lady forward long before the fortuitous winds of change were in her favour. She stood up for Indigenous ‘self-determination’ to reinstate the basic rights Anishinaabe women lost when they married non-native men. Her commitment to change was initiated by the loss of her own rights two weeks after she married musician and filmmaker David Lavell. In 1972, Jeannette won a case at the Ontario Court of Appeals. After her one-vote defeat on her national effort to change this particular part of the Indian Act at the Supreme Court of Canada in August of 1973, Jeannette regained strength from her father’s words: “Don’t worry about the people who say ‘no’; fight for what you believe to be right.” Her commitment and perseverance paid off. In 1985, she and five supporters won the legal right under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms to change Section 12-1-B of the Indian Act to regain Indian status rights for thousands of Indigenous women in Canada who, like Dr. Corbiere Lavell, had been denied their heritage because of the choice of marriage partner.

She began the fight for change with a few of her own Indigenous decisionmakers, comfortable with the status quo. “Six of the National Indian Brotherhood chiefs claimed we were destroying the Indian Act. Some of these decision makers had mixed marriages in their own families and didn’t want their Zaaganash (non-Native) wives to lose benefits from the Canadian government. The Attorney General of Canada, the Six Nations’ chief and one other chief contested the proposed changes.”

“It was pure gender discrimination that had been built into the Indian Act, because ‘that’s the way it has always been done in the past’.” In 1971, Indigenous women were beginning to form their own organizations, like ONWA, Ontario Native Women’s Association. Local ‘Breaking Free’ groups were challenging the men on the reserves and the government. In 1982, Pierre Trudeau introduced the new Canadian Constitution, which opened a few doors. After her landmark ruling was achieved in 1985, through the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Jeannette continued to champion the rights of Indigenous women through the Charter and as a founding member and president of ONWA.

Jeannette has also been promoting women’s rights at the Organization of American States, the United Nation Human Rights Committee, the Committee to End Sex Discrimination and at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Through this continued advocacy, Jeannette became a powerful role model for Indigenous women. Over the years, she has won many accolades for her successes, including the Person’s Case Award in 2009 which recognizes all persons, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, who fight for women’s rights in Canada. In 2017, she was awarded the Order of Canada. A Lifetime Achievement Award under the Indspire banner was presented in 2020.

“Tracing our ancestry back a few generations through church records, the name Assiginack (Black Bird), an interpreter of the 1836 and 1850 treaties, comes up. The former was the treaty that Wiikwemkoong never signed, making them an ‘Unceded’ Reserve. Assiginack is buried in Manitowaning. Makade Kek (Chief Black Hawk), the name of another broker who features in early political change also came up. About the time of the war of 1812, tribes in northern Michigan, fearing attacks from Americans because they had supported the British side, moved further north to Canada. Dr. Cecil King’s book ‘Between Two Worlds’ is a source of more information about this time.”

“My maternal grandmother is Mary Jane (Pangowish). She is related to both Assiginack and Makade Kek, and she came from Cross Village in Michigan to settle in Canada where she met and married Michael Antoine Trudeau, Mishenaatwen, a renowned boat builder of Mackinaw boats. He was also a good carpenter and fisherman. His boats travelled to Tobermory from Manitoulin and all along the North Shore.” (Many northern Michigan tribes had assisted the British forces in the War of 1812, the new US nation’s attempt to annex British North America.)

“Dad’s Corbiere side originated in Southern France. French soldiers came to North America to fight the English over territory. After the fighting ended, French soldiers were given the choice to stay or go back to France. We believe dad’s ancestors stayed and moved to Upper Canada after the war of 1812. Dad’s ancestor, Louis Corbiere, settled close to an Ojibwe tribe near Coldwater (between Orillia and Midland) where he married a Potawatomi bride. From there, Louis and his wife moved to Drummond Island. He became a trader and M’Chigeeng was part of his territory. Our Grandfather, David Corbiere, was born in M’Chigeeng where his mother lived. He farmed and married Mary Jane Assinewai in Wiikwemkoong.”

“My mother, Rita Trudeau, was 24 when she married Adam Corbiere, David’s son, in 1939. Adam was a self-taught man with many skills. He had learned English through interactions with the English-speaking settlers. He was hidden when the residential school scouts arrived, so didn’t attend the residential school. My mother was one of the first women in business and my role model,” Jeannette continues. “She attended the Indian residential school for girls at Spanish where the cold and hunger pangs were somewhat mitigated by the presence of her two Anishinaabe-speaking sisters.”

“She left the school at Spanish, returned to Wiikwemkoong and later spent four years at a residential school in Pembroke. Afterwards, she attended normal school (teachers college) and became a teacher in Wiikwemkoong, balancing her domestic role with that of a professional teacher at the Indian Day School, run by the Department of Indian Affairs. After she married our father, she had to quit teaching because that was the custom then. She developed her artistic side and created beautiful paintings and porcupine quill baskets. One of her five-inch quill boxes featuring a small skunk was accepted by the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C. Dad was working in Killarney, blasting rock, biignen. He would get into his boat on Sunday afternoon or Monday morning and return Friday night.”

Rita and Adam bought a grocery store from friend Ernest Debassige and Rita became even more of a businesswoman. “Dad soon learned about the financial end from mom, and he became good at it. He never learned to read but he found ways to compensate. In a restaurant, gazing at the menu, he would ask, ‘who can find this meal?’ and we would find it for him. Dad drove a truck for the local lumber companies, and he drove the school bus. When Prime Minister Lester Pearson visited Wiikwemkoong, chief and council chose dad, who owned the best car, a big Buick, to pick him up.”

He and Rita became the parents of four: Jeannette, Robert, Elaine, and Richard. “I was born June 21, 1942, on the longest day of the year, and I was the shortest baby of the four. Being born at the summer solstice seemed to gain a lot of attention from aunts and uncles, I soon found out. One early story that my aunt always mentioned happened when I was six or seven. It was a snowy morning. Mother insisted I wear my snow bloomers that stretched over my dress. I protested, but to no avail. I put on my rubber boots and headed for school with our little dog in tow. I walked in the ruts left by the horses and the wagons and marched along, right past the schoolhouse into the great beyond.”

“When I didn’t come home for lunch, my parents began to search. One elderly gentleman told my parents he had seen the top of a little girl’s head, followed by a dog heading for Manitowaning. I had deliberately avoided school, with those bloomers on, and had reached Auntie Mary Corbiere’s home. She put me into her cutter and headed out. At the end of the driveway, we met the big horses and the box wagon looking for me.” Jeannette was already showing early sign of a strong-willed, independent spirit.

“I was the pet girl too. I liked to find stray cats and dogs and always had animals around me. Mum’s rescue dog adopted me too and I added a stray cat, ‘Snowball,’ to the family. They slept with me at night. Snowball even had a little kitten in my bed.”

“Milk always gave me an upset stomach. I likely had a lactose allergy but that was less known then, so I just avoided milk. I liked vinegar and pickles, though. Grandfather David Corbiere had a contract to feed about 50 workers manning the log barges that docked in South Bay. My parents would arrive to prepare large quantities of food. I remember being six and very near to a barrel of pickles. I rigged up a chair and climbed up to gaze into the open pickle barrel. My arms stretched deeply inside, trying to grab a pickle. If someone hadn’t spotted me, I surely would have gone head-first into that barrel.”

“Santa was not a mystery for long. Robert, Elaine and I were about five, six and seven when Santa arrived at our home after church and the big traditional midnight supper. Peter Owl, a relative who worked at the store and could easily be mistaken for Santa, made an appearance. I recognized his rubber boots. “’That’s Uncle Peter!’ I blurted out with conviction. I guess I spoiled the fun for my younger siblings.” Jeannette sighs. She perks up again, “There was a twenty dollar sweetheart watch in the Eaton’s catalogue and I really wanted it. I wrote to all my uncles and each one sent money, enough to buy the watch. That was my first big, treasured piece of jewellery.”

“Brother Robert worked on the big lake boats first, then ran the grocery store and drove the school bus, before becoming the band administrator and later chief of Wiikwemkoong. Sister Elaine Brant-Hoy became a secretary for a technical company in Toronto. She also became a teacher, like her sister and her mother. Richard, the youngest sibling, was an accomplished artist until he died unexpectedly in May of 2020. He had been a student at Tom Peltier’s Schreiber Island Project, an art school held at a North Channel Island in the early 1970s and had travelled to Europe as part of an art exchange. He painted masks, made deer hide jackets, bone carvings and painted murals on buffalo hides which sold for thousands of dollars.”

“I learned my English from my mother, the teacher and Anishnaabemowin from my father. Knowing both languages gave me the job of official interpreter for the nuns at the school. Despite this, the first five years were not remarkable for me. I had difficulty learning. In Grade 5, Sister Veronica of St. Joseph’s School came to my rescue. She put me into her ‘special’ class and spent more one-on-one time with me. Looking back, I think my creative side, the right side of my brain, was also developed with her teachings. My marks went from zero to 98 percent and I mastered cursive writing, all in one year.”

“After Wiikwemkoong, I attended high school at St. Joseph’s College in North Bay and finished Grade 12. I was glad that my friend Evelyn Corbiere was there too.” The College was followed by St. Mary’s Academy School, also run by the Sisters of St. Joseph in North Bay. When school was over, Jeannette returned to Wiikwemkoong and spent her first summer as a secretary for the local Indian Agency in Manitowaning. The agency also included the RCMP, a nursing residence and a hospital. “I was filling in for a maternity leave.” After the summer, Indian Affairs got Jeannette a job in Toronto working for an insurance company on Bay Street. She roomed with her friend Priscilla Hill. “The people were nice, but the work was not purposeful enough.”

In the early 1960s, Jeannette took time off to take business courses. The new Canadian Indian Friendship Centre was being set up on Church St. in Toronto and they were looking for staff. “I got my first job as a court worker. I knew the language and got on-the-job training about the legal system. The work was heartbreaking and opened my mind to a new world. Anishinabek people from the North and from the Six Nations community living in downtown Toronto had many struggles, including homelessness and drug-use. The only supports that existed were the new Friendship Centre and the Toronto Indian Club which held dances and banquets.”

In 1965, while still dealing with the court system, Jeannette was asked to enter the Indian Princess contest. She was 23 when she won the title for Canada. “In 1968, I joined the Company of Young Canadians (CYC), set up by Martin O’Connell, and worked as a trainer in Western Canada for about two years.” In 1969, while working for the Native Friendship Centre, she met tall, handsome David Lavell who volunteered to play his music at the centre. He was a student of journalism and photography at Ryerson.”

Jeannette and David were married on April 11, 1970. “I remember the music starting, and David and I were to lead off the first dance. I saw him on the stage, and we exchanged a glance. His uncle quickly came up to me to take David’s place for that first dance. David did join me a little later. There was no time for a honeymoon.”

“Two weeks after the wedding, I was notified by Indian Affairs that I was no longer a member of the Wiikwemkoong Reserve. I got a cheque for $35 which I never cashed. This was the beginning of my long journey to regain the rights of women who had married non-Indigenous men. I had met many people across Canada through the CYC, and I was aware that many women had been affected by this ruling. “Clayton Ruby, a young lawyer, would become a strong voice in the upcoming years of regaining our rights. David and I were both students, but we knew we had to challenge this law right away and Clayton took it on pro bono. We put our appeal in the next day, just one day prior to the deadline.”

Jeannette began to give workshops dealing with cross-cultural issues. In 1974, she attended teacher’s college and got her teaching degree. At this point she and David moved to the Island, to Wiikwemkoong, and Jeannette taught elementary Grades 5 and 6. Later, she was one of the first teachers to provide classes in fine art and photography, business and parenting at the high school level. She was one of the original staff members of Wikwemikong High School.

In the 1980s, the couple bought a 200-acre farm near Blue Jay Creek in Tehkummah Township. “Our neighbour Wendel Arnold leased our land. He had a big black draft horse. We had a little western riding horse, a gift from Bobby. One morning, we woke up to a lot of snorting. Our small horse was challenging the big horse. The big horse soon jumped the fence and began chasing our horse around the field in a big circle. Lots of noise and shaking ground ensued and we ran inside. Finally, both animals tired and could be separated again.”

The couple had three children, Michael Nimkii (Thunder), Dawn Waubmemee (White Dove) and William Ahzbik (Mountain). “Nimkii was one of the first to be registered with an Anishinabek name and he works as a land-based teacher. Dawn has been the president of the Ontario Native Women’s Association for 22 years. She recently stepped down and now works as director of the Indigenous House of Learning at Trent University in Peterborough and as a professor. She is highly creative too. William works for the United Nations, travelling to refugee settlements, globally.” Twenty years ago, David and Jeannette decided to go their own ways. David has remarried now.

“Special events? The Native Women’s Association of Canada invited Jeannette and Memee (Dawn), as Anishinaabe Representatives of Canada to attend an Indigenous award ceremony in Geneva for Riguberto Menchu, who had won the Nobel Peace Prize. “It was a distinctive honour in which to participate and we were also invited to the private home of the Canadian Ambassador for dinner that night.”

“Any stories from elders to share? Andrew Mandamin describes water tunnels under Manitoulin. He said the lakes and waterways were all connected. A trout tagged in one lake showed up in another lake. ‘The water spirits must be respected,’ he had said. In the 1950s, one young man crossed Manitowaning Bay but never made it to shore. It was alleged that earlier he had disrespected these water spirits.”

“Favourite teacher? Sister Veronica who woke me up to a successful academic life. Strengths? I like to follow the Grandfather Teachings. Bravery comes to mind. Teachers, and later Anishinaabe women, encouraged me to take the lead and maintain that path until the finish. Projects that interest me now? Retaining our language for our young people. Jack Wemigwans of the WHO (Wiky Heritage Organization), and Amikook, the elder’s centre, supports this too.”

“I am also anxious to learn more about our traditional crafts. I am hoping to add finesse to the quill boxes I can make. Painting pictures is something I would like to do more of as well.”

If you could keep only three items from your current life? “They would be my crafts-paints, my books, and my gardening tools.”

Going back in time is there anything you would change? “No, I am happy with the life I had and have now.”

“What am I proud of, besides my family? The early work that strengthened Indigenous women’s roles and rights led to many positive changes that took on a life of their own, like the National Inquiry of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. ONWA now has a $20 million budget doing work at the community level, work like training members how to deal with violence. Another positive change was the Union of Ontario Indians (UOI) recognizing the voices of the Anishinabek women.” About 12 years ago, Jeannette was invited to be the UOI Commissioner of Citizenship for the Anishinabek Nation. This role sprang from the 1985 Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms ruling that allowed thousands of men and women, to regain their Anishinabek citizenships, ‘E’Dbendaagzijig Naknigewin.’

Today, Jeannette and her son Nimkii, Shelly, River and Gryffyn live in Manitowaning, close to the Debajehmujig Theatre, where she is a member of the board. She is still involved with political circles that remain from her activist years. Her knowledge and connections continue to help move issues forward for her people. “Right now, we are also still dealing with COVID on Manitoulin. I encourage people to drink tea from sweet fern and cedar, gaabaagemish, regularly. It helps to fight inflammation and infection.”

“I am very thankful to the Creator and our ancestors. I have three beautiful children, adults now, and seven grandchildren. There is a sense of belonging to this community and this Island, ‘E’obendaagzijig,’ that makes it special to me. Manitoulin has been my family’s home for two hundred years and will continue to be now and forever.”