by Alicia McCutcheon with files from Shelley Pearen

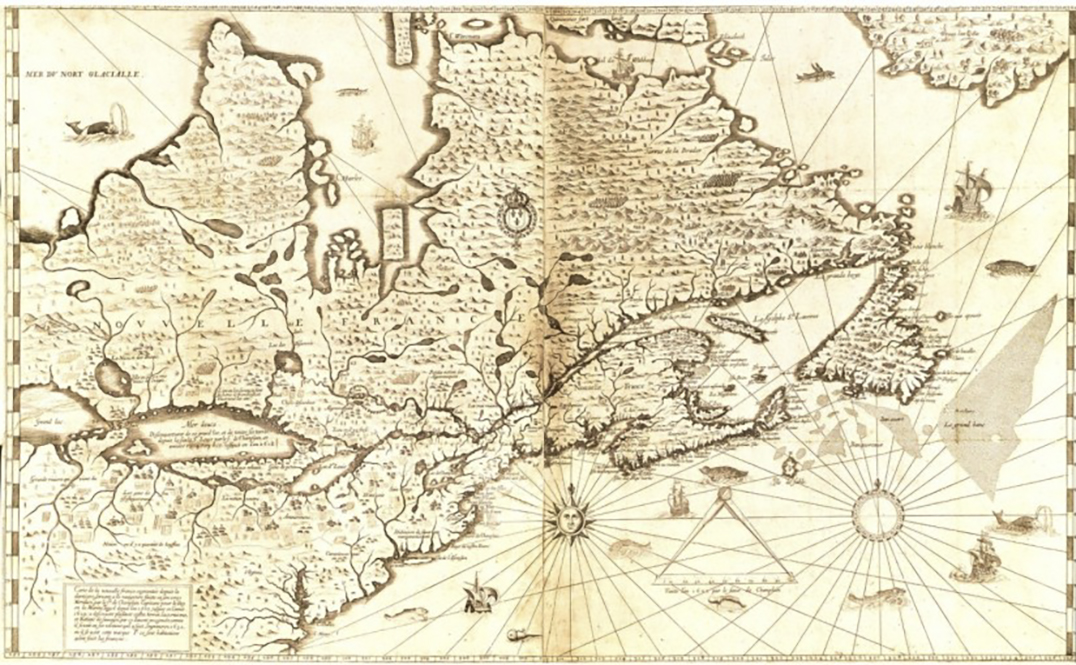

SWIFT CURRENT— It was 400 years ago, August 1, 1615, that famed French explorer Samuel de Champlain travelled the waters near Manitoulin Island, likely setting foot on land near Swift Current (at the LaCloche causeway on present-day Highway 6) and meeting with local First Nations people as he became the first explorer to tour the Great Lakes region.

The following is an excerpt from Champlain’s diary ‘Voyages et descouvertures faites en la Nouvelle France depuis l’annee 1615’ and printed in 1870 by Desbarats (and translated by historian Shelley J. Pearen).

“After spending two days with the chief they call Nipisierinig: we re-embarked in our canoes and entered a river by which this lake discharges and were some 35 leagues, and descending several rapids, as much by land as by water, to lake Attigouautan. This country was more disagreeable than the previous, for there was barely ten acres of workable land, rocks and mountainous region. It’s true that near the lake the Attigouautan found “bleds d’Inde” [villages = bleds, but more likely means ble = corn], but in small quantities; where our Natives were taking pumpkins which seemed good to us, for our provisions were starting to be lacking from feeding the Natives who ate so well at the beginning, that at the end little remained, having only one meal a day. It’s true as I’ve said above, that the blueberries and strawberries were not lacking, as formerly we had been in danger of having them out of necessity.”

“We met 300 men of a nation that we have named the cheveux relevez, for having raised and constructed, and better coiffured hair than our courtesans, and having no comparison, some irons and way that they could supply them. They have on way to “brayer” and make strong cutting by the body in several ways to compartments. They paint their faces in diverse colours, have pierced nostrils and ears edged with patinostres. When they leave their houses, they carry a club i.e. they visit and familiarize rarely and make friends with them. I gave an axe to their chief, who was satisfied that I had given such a good present and communicated with him, I asked him about his country. He drew with charcoal on bark from a tree. He told me that they came to this place to dry this fruit called blueberries for the winter but they had not found any. A.C. showed the way that they arm themselves going to war. All they have is the bow and arrow, but it is made in a way that “voyer depainte” that they usually carry and a rondache of boiled skin, which is from an animal like the buffalo.”

“The next day we departed and continued on our way the length of the shore of this lake of the Attigouautan, where there are a large number of islands, and about 4.5 leagues, along this lake. It is very large and about 400 leagues long from east to west, and 50 leagues, I’ve named it La Mer Douce (present-day Georgian Bay). It is abundant is several species of very good fish, some we have, some we don’t, and principally trout which are monstrously large…”

According to the Ontario Heritage Trust, on April 24, 1615, Champlain, Captain Pont Gravé and four Récollet fathers departed for New France aboard the Saint-Étienne. They arrived at Tadoussac on the St. Lawrence River near the end of May and continued on to present-dau Quebec City. There, Champlain quickly dispatched orders to the habitants and continued up the St. Lawrence to the Rivière des Prairies, where he was greeted by a large group of aboriginal people, including members of the Huron (Wendat) and Algonquin (Anishinabe) nations. They asked Champlain to assist them in their campaign against the Onondaga and Oneida nations, which posed a constant threat to fur trade routes along the upper St. Lawrence and Ottawa rivers.

Having agreed to participate in the campaign, Champlain hurried back to Quebec to make the necessary arrangements. He was late meeting his aboriginal allies at their agreed-on location but continued regardless, travelling first up the Rivière des Prairies and then along the Ottawa River to Morrison Island. His party then travelled to the Mattawa River and across it and other waterways to today’s Lake Nipissing. Throughout his travels, Champlain met with a number of aboriginal nations and worked to promote alliances with the French. After meeting with the Nipissing nation, he travelled along the French River into Lake Huron and finally southwards across Georgian Bay to a site near present-day Penetanguishene.

Champlain spent much time exploring Huronia (the present-day Midland-Penetang area) and visited a number of the villages of the Huron confederacy, including Carhagouha, recording his observations and impressions as he went.

It was Champlain’s extensive record-keeping that drew Anishnaabe historian and Wikwemikong Director of Education Dominc Beaudry to him.

“He met the Odawa at the mouth of the French River, probably on August 1, 400 years ago,” Mr. Beaudry explained.

While researching documents at the University of Toronto archives, Mr. Beaudry said he was interested to find that in some letter to France he would write about the poor conditions of the First Nations people, asking for more money to better their life, while a mere two paragraphs later he was remarking on the two leagues (six miles) of corn planted and a mile-and-a-half of potatoes at the First Nations community of between 250 and 300 people where modern-day Cobden, Ontario (near present day Petawawa) stands today.

“That’s a lot more than they consume, which leads me to believe that there was a strong, economic community (among the tribes),” he said. “Champlain created a clear economic picture of who the First Nations really were—quite an involved agriculture community to the Great Lakes region, and that’s 400 years ago.”

Yet, he said, ironically in 1890 the Canadian government decided the First Nations people of the same region Champlain had explored needed to be civilized and learn how to become good farmers and work the soil.

“For a lot of us living in the Great Lakes region there is lots to learn,” Mr. Beaudry continued. “We are all Canadian and when we write Canadian history we need to make that right.” The “bits and pieces” Champlain provided in his writings paint a picture of a proud and healthy people who drove a healthy economy “and First Nations people today should take a lot of pride in the fact that their ancestors would work the land and fisheries.”

“We talk about reconciliation, but one needs to understand that First Nations had an affect on the Europeans too,” Mr. Beaudry added, noting that one of the driving factors behind the success of the Industrial Revolution in Western Europe is the fact that, by that time, Western Europe had become a modern agrarian society planting the muss-free crops of wheat, rice, corn and potatoes (introduced by North America’s indigenous peoples) which meant more time for industry, and change.

“Despite the negative impacts, it is part of our history and his writings are a positive for those who seek to make a new history,” Mr. Beaudry concluded.