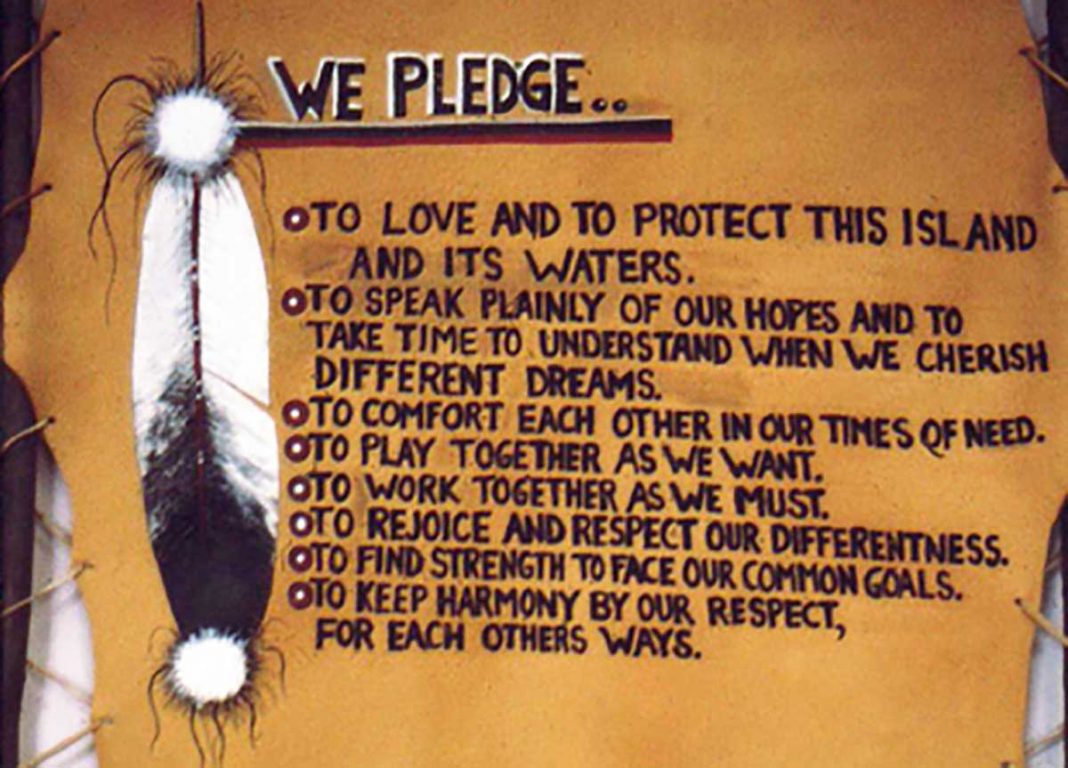

MANITOULIN – While work continues on forming a cross-Island COVID-19 leadership co-ordination committee, some Islanders may recall a time when the collaborative spirit was celebrated during another tense period that led to the signing of the 1990 Friendship Treaty, the Maamwi Naadmaading Accord.

“Our hope was just to set the tone to let everyone know that we were willing to work jointly on things that would benefit both (First Nations and municipalities). We were not as concerned about looking after individuals as we were looking after the area as a whole,” said Thomas Farquhar Jr., then-reeve of Carnarvon Township (now a part of the Municipality of Central Manitoulin) and then-chair of the Manitoulin Municipal Association (MMA).

His name appears as one of the two lead signatories on the original treaty, based on a photo sourced from conservation architect François LeBlanc’s website about the Manitoulin Island Mnidoo Mnis Heritage Region Project.

The MMA and the United Chiefs and Councils of Manitoulin (UCCM, which later became the present-day UCCMM) were the two lead organizations that signed the treaty.

It helps to understand some of the context of the time. Although this newspaper’s microfiche archives are currently inaccessible due to their location in the temporarily closed Little Current Public Library, discussions with Island leadership from that time have highlighted some of the context behind the original document.

In 1990, several First Nations on Manitoulin Island were working through a land claim based on unresolved issues stemming from the 1862 Manitoulin Treaty. Part of the negotiations involved municipal road allowances and questions of lost tax revenue for municipalities.

“We were trying to get some co-operation among the municipalities to work with us on pressuring the government to get some movement on these things,” said Pat Madahbee, then-chief of Sucker Creek First Nation (now Aundeck Omni Kaning).

“I have to say, during this process, the province could have stepped up a lot better informing municipalities; (the municipalities) were in the dark on a lot of things surrounding the land claim at the time,” said Mr. Madahbee.

While Mr. Farquhar said he was unsure of whether or not the treaty changed the working relationship between First Nations and municipalities, it certainly opened more communication.

“It sent a message to Queen’s Park and the federal government that we were willing to step up and work together to benefit the Island as whole, and not any of us individually,” said Mr. Farquhar.

While Mr. Madahbee said there was not always agreement on the issues, it was certainly better to have dialogue.

“Co-operation works. Even within the towns and communities themselves, their leaders will never get 100 percent agreement … I’ve experienced that in my leadership capacities over the years,” he said. Mr. Madahbee is also the past Grand Council Chief of the Anishinabek Nation.

Some of the important issues in those discussions were tourism and the health and well-being of the Island as a whole.

Discussing issues in the modern day, however, is complicated by the rise of social media and the ability for anyone, even anonymously, to share strong opinions regardless of whether or not they are rooted in fact. This is especially evident in threads about the M’Chigeeng travel restriction.

“I think the biggest issue here is stupid Facebook; I call it two-face book,” said Mr. Madahbee, who added that discussions should move beyond just the economy to considering the overall health and well-being of a community.

Mr. Farquhar shared a similar sentiment.

“I’d hope that the issues that the municipalities and First Nations are faced with today … will be dealt with as effectively as possible in either case, whether it be by local government and First Nations or by the joint group. If there’s more benefit to the Island to do it jointly, I’d hope that’s where they’d go,” he said.

“These are people’s lives we’re dealing with, and to deal with that we have to put ourselves in the position of people who might be suffering,” said Mr. Farquhar. “And the one thing I’d like to say, I don’t see any particular First Nation or municipality making any moves to improve their circumstances more than anybody else’s. I think there’s a willingness to work jointly, it’s just a matter of what they can get done.”

Perhaps some of the lessons learned 30 years ago are even more relevant in 2020 as Manitoulin faces the COVID-19 pandemic, with a formalized structure of dialogue between communities offering a possible path to greater collaboration and the improved health of the Island as a whole.